Event-driven Architecture — Everything You Need to Know

Event-driven architecture is a common pattern found alongside micro-services and other decoupled services or apps. In an event-driven…

Event-driven architecture is a common pattern found alongside micro-services and other decoupled services or apps. In an event-driven architecture, each service in an ecosystem reacts and takes action upon an event it receives. There are both upsides and downsides to event-driven architecture but before we get into that, let’s take a look at an example of how event-driven architecture works so you know exactly what it is.

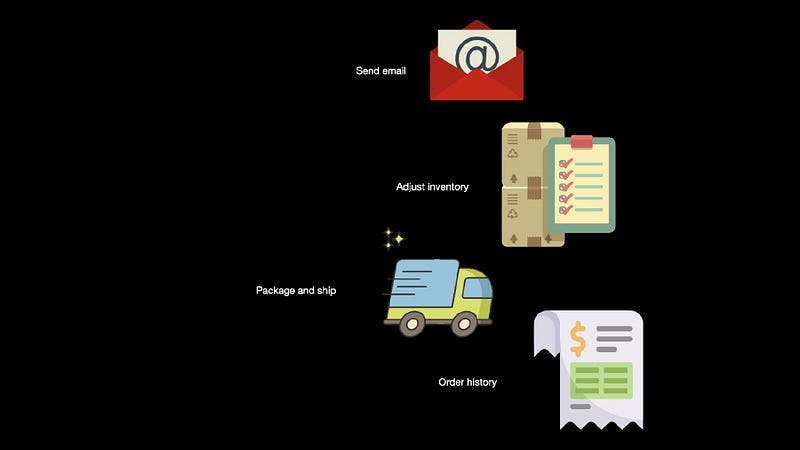

Let’s say we have a standard eCommerce system that allows users to purchase a product on a website. When a purchase is completed, several things need to happen.

An email receipt should be sent to the purchaser

Inventory numbers should be updated to reflect that there are now less of the product available for purchase

A fulfillment system needs to be notified so the purchased product can be shipped

A purchase history should be updated for both the customer and the company to use for later reference

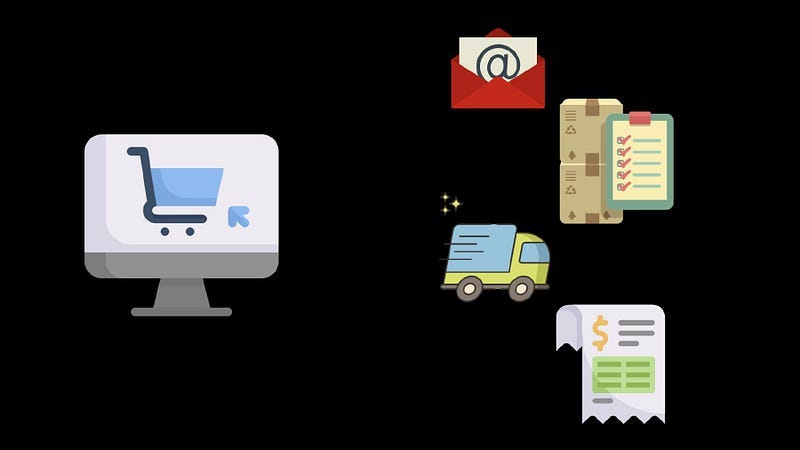

So it looks like we need to have five services to make all of this work.

The eCommerce system itself for taking the money

A service that sends emails

An inventory control service

A fulfillment service

An order history service

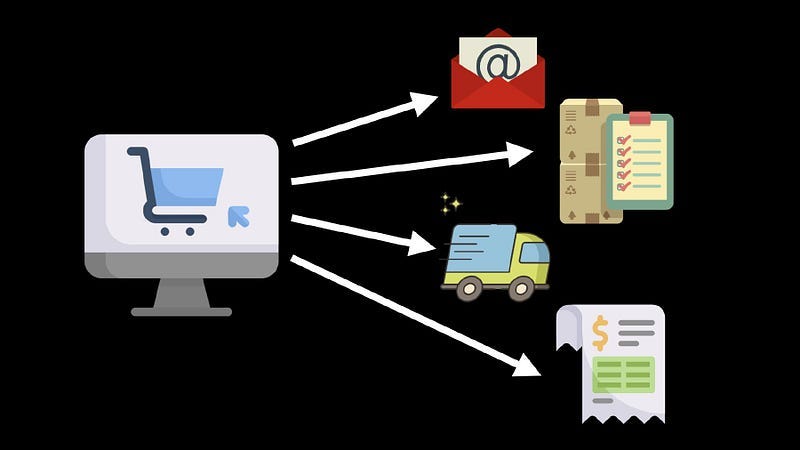

In a more traditional service-to-service direct communication architecture, the eCommerce service would complete the purchase with the customer then several point-to-point calls would be made. It would call each of the other four services, likely using a REST API, to tell those services to complete their actions.

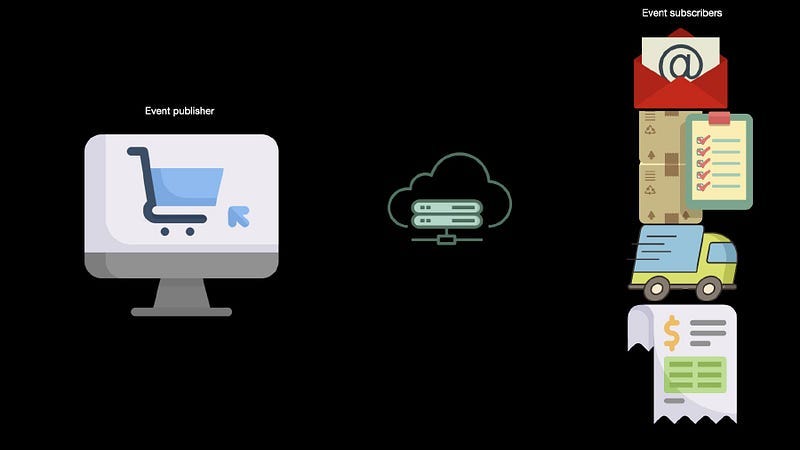

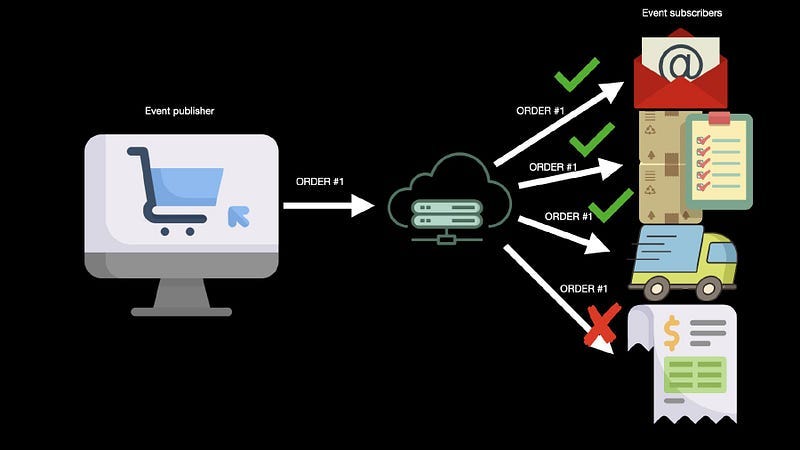

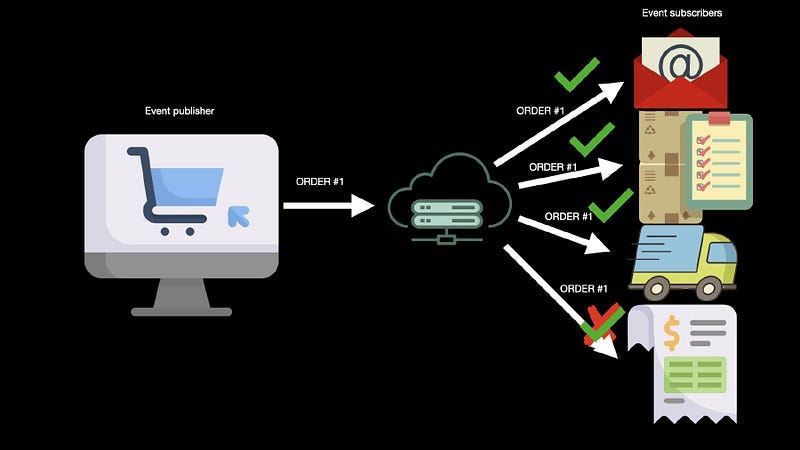

Now, in an event-driven architecture, we would eliminate that point-to-point relationship between all of these services. instead, we’ll introduce another service which we’ll refer to as an “event router”. This event router can receive events from event publishers and it will push events to event subscribers. There are many different brands of event routers out there and ill talk about that in just a bit but for now, let’s keep going with the example.

So let’s rearrange the diagram. In this new event-driven setup, the eCommerce system becomes the event publisher and the other four systems become the event subscribers.

In this setup, the eCommerce platform no longer needs to make several outbound calls to each service with instructions on what to do. Instead, after the purchase is completed, it sends an event to the event router. This event indicates that a purchase has been completed as well as any other necessary details about the completed purchase that are necessary to allow the other services to complete their task.

After the event router receives the event, it then pushes the event details to the event subscribers or the subscribers pull the events from the router (both options are usually available). When each of the four subscribers receives the events, they complete their necessary tasks and then acknowledge to the router that they’re done.

At this point, the same outcome has been completed between these two different setups, but in slightly different ways.

So, now that you know what event-driven architecture is, let’s discuss why you would want to do this. After all, it kinda looks like I added more complexity here because I added a sixth service to the stack.

And you’re right. I did add another service here but following this pattern has some huge upsides compared to the point-to-point method. I think the first thing we should discuss is how event routers and queuing services greatly reduce the possibility of system failures.

In the example above I kinda breezed through the part where the event subscribers acknowledge that they have completed their tasks. This feature is a key trait of an event-driven architecture. You see, when the router receives an event, it knows which subscribers should receive that event and they must acknowledge they have completed their task. When the router attempts to send the event to the subscriber, if the subscriber doesn’t reply and say “all set here”, the router will retry sending that event until it has been acknowledged. This means that one of your subscribers could be completely down for even an extended amount of time and still receive all of its events when it comes back up, ensuring consistency between your systems. Most event routers even have the capability of reporting when an event fails too many times and it gives up on sending an event. Not ideal, but this does allow for engineers to fix the issue and also allows for manual remediation of the event that failed.

Note that not all routers support subscribers and queuing of tasks as one service. I’ll cover that later.

In the point-to-point approach, the commerce system would have to know how to handle failures and attempt to retry the API calls until they succeeded. If this is an extended amount of time, this could cause the eCommerce system to slow down or crash as it attempts to remember and retry all of these requests until they are complete. this can cause slowdowns for the end user or even a complete service failure.

The second major advantage of an event-driven architecture is related to maintaining a decoupled relationship of micro-services or separation of duties. Let’s start on the publisher’s end. In our example, the eCommerce system’s responsibility in this process is greatly simplified. All the eCommerce system needs to do here is publish a single event to the event router. It no longer needs to be concerned about what happens next.

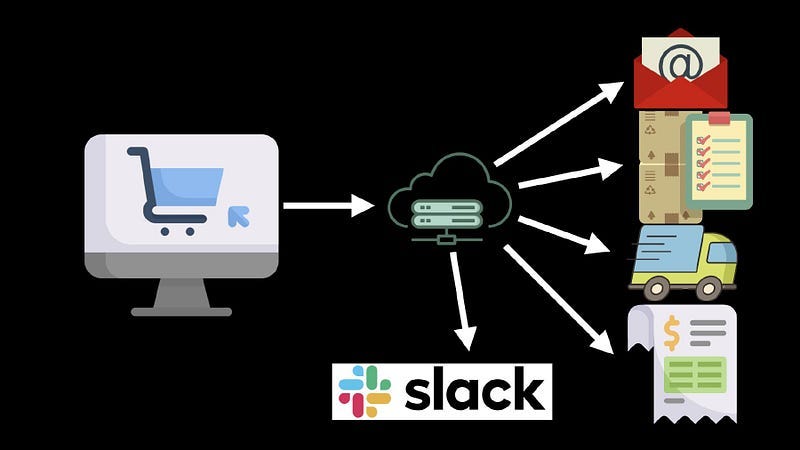

Because of this, we can now easily add additional subscribers to this process with zero changes to the eCommerce system. Let’s say we wanted to create a service that alerts the store owner of a purchase via slack. Well, that’s no big deal now. Just add slack as a subscriber to the event router and it will also start to receive events about new orders.

On the flip side of that, what if we wanted to completely replace our eCommerce system with something new? Well, as long as that new system can publish events about new purchases, zero changes need to be made to the subscribers.

So those are the plusses to event-driven architecture, but there can also be some downsides.

The biggest downside to event-driven architecture is that everything is real-time. And while that can be also a plus, ill explain where it causes a problem. Let’s say that you want to introduce a system that maintains the user profiles of your customers. You add this new service as a subscriber to your router and now each new purchase shows up on the user’s profile. well, that’s great but what about the purchases they made last year?

In this scenario, you would need to do some additional work before you could just set it and forget it. You would likely need to batch load all of the previous order histories into the new system and then add it to the router so it can get all new orders. As you can see, it can take some planning to ensure you get everything in sync, but moving forward you will enjoy the benefits of the event-driven system.

So I promised earlier that I would cover the brands of event routers out there. As usual, all of the major cloud hosting companies have their own flavors of event routers.

AWS has SQS and SNS. It’s mainly a difference between persistence and guaranteed deliverability. Often you may end up using both.

GCP has PubSub which is my personal favorite. It’s kind of a combination of both AWS services and it allows for multiple subscribers with guaranteed deliverability in both a push and a pull setup.

Beyond the cloud providers, there are also open-source event routers out there. A couple of these are Apache Kafka which is highly configurable and can do lots of fun stuff when configured correctly.

And RabbitMQ which I honestly have never used but I didn’t want to leave it out because it’s a very well-known product in this space.

So there you have it. That’s everything you need to know to get started with an event-driven architecture. If you liked this video leave me a like and if you have questions or comments please leave them below.

Until next time, happy coding!